Is materials science the new alchemy for the 21st century?

It can be challenging to define exactly what materials science is all about. But Honor Powrie believes the field is the most rewarding and challenging in all of science, with its practitioners striving to create “new gold”

|

Stuff that matters Whether it's metals, ceramics, bioplastics or the auxetic materials in this Nike running shoe, the world is being transformed thanks to materials science. (Courtesy: Ethan Jull, University of Leeds)

For many years, I’ve been a judge for awards and prizes linked to research and innovation in engineering and physics. It’s often said that it’s better to give than to receive, and it’s certainly true in this case. But another highlight of my involvement with awards is learning about cutting-edge innovations I either hadn’t heard of or didn’t know much about.

One area that consistently fascinates me is the development of new and advanced materials. I’m not a materials scientist – my expertise lies in creating monitoring systems for engineering – so I apologize for any oversimplification in what follows. However, I would like to give you a sense of just how impressive, challenging, and rewarding the field of materials science is.

It’s all too easy to take advanced materials for granted. We are in constant contact with them in everyday life, whether it’s through applications in healthcare, electronics and computing, or energy, transport, construction, and process engineering. But what are the most important materials innovations right now – and what kinds of novel materials can we expect in the future?

Drivers of innovation

There are several – and all equally important – drivers when it comes to materials development. One is the desire to improve the performance of products we’re already familiar with. A second is the need to develop more sustainable materials, whether that means replacing less environmentally friendly solutions or enabling new technology. Third, there’s the drive for novel developments, where some of the most groundbreaking work is occurring.

On the environmental front, we recognize that many products contain components that could, in principle, be recycled. However, the reality is that many products end up in landfills because of how they’ve been constructed. I was recently reminded of this conundrum when I attended a research presentation on the challenges of recycling solar panels.

Green problem: Solar panels often fail to be recycled at the end of their life despite containing reusable materials. (Courtesy: iStock/Milos Muller)

Photovoltaic cells become increasingly inefficient with time, and most solar panels aren’t expected to last more than about 30 years. Trouble is, solar panels are so robustly built that recycling them requires specialized equipment and processes. More often than not, solar panels are simply thrown away, despite mostly containing reusable materials such as glass, plastic, and metals – including aluminum and silver.

It seems ironic that solar panels, which enable sustainable living, could also contribute significantly to landfills. In fact, the problem could escalate significantly if left unaddressed. There are already an estimated 1.8 million solar panels in use in the UK, and potentially billions around the world, with a rapidly increasing install base. Making solar panels more sustainable is surely a grand challenge in materials science.

Waste not, want not

Another vital issue concerns our addiction to new technology, which means we rarely hang on to objects until the end of their life. I mean, who hasn’t been tempted by a shiny new smartphone, even though the old one is perfectly adequate? The urge for new objects means we need more materials and designs that can be readily reused or recycled, thereby reducing waste and promoting resource conservation.

As someone who works in the aerospace industry, I know firsthand how companies are trying to make planes more fuel-efficient by developing composite materials that are stronger and can survive higher temperatures and pressures – for example, carbon fiber and composite matrix ceramics. The industry also uses “additive manufacturing” to enable more intricate component design with less resultant waste.

Plastics are another key area of development. Many products are made from a single type of recyclable material, such as polyethylene or polypropylene, which benefit from being light, durable, and capable of withstanding chemicals and heat. The trouble is, while polyethylene and polypropylene can be recycled, they both create the tiny “microplastics” that, as we know all too well, are not good news for the environment.

Sustainable challenge Material scientists will need to find practical bio-based alternatives to conventional plastics to avoid polluting microplastics entering the seas and oceans. (Courtesy: iStock/Dmitriy Sidor)

Bio-based materials are becoming more common for everyday items. Think about polylactic acid (PLA), which is a plant-based polymer derived from renewable resources such as cornstarch or sugar cane. Typically used for food or medical packaging, it’s usually said to be “compostable”, although this is a term we need to view with caution.

Sadly, PLA does not degrade readily in natural environments or landfills. To break it down, you need high-temperature, high-moisture industrial composting facilities. So whilst PLAs come from natural plants, they are not straightforward to recycle, which is why single-use disposable items, such as plastic cutlery, drinking straws, and plates, are no longer permitted to be made from it.

Thankfully, we’re also seeing greater use of more sustainable, natural fibre composites, such as flax, hemp, and bamboo (have you tried bamboo socks or cutlery?). All of which brings me to an interesting urban myth: in 1941, legendary US car manufacturer Henry Ford built a car apparently made entirely of a plant-based plastic – dubbed the “soybean” car (see box).

The soybean car: fact or fiction?

|

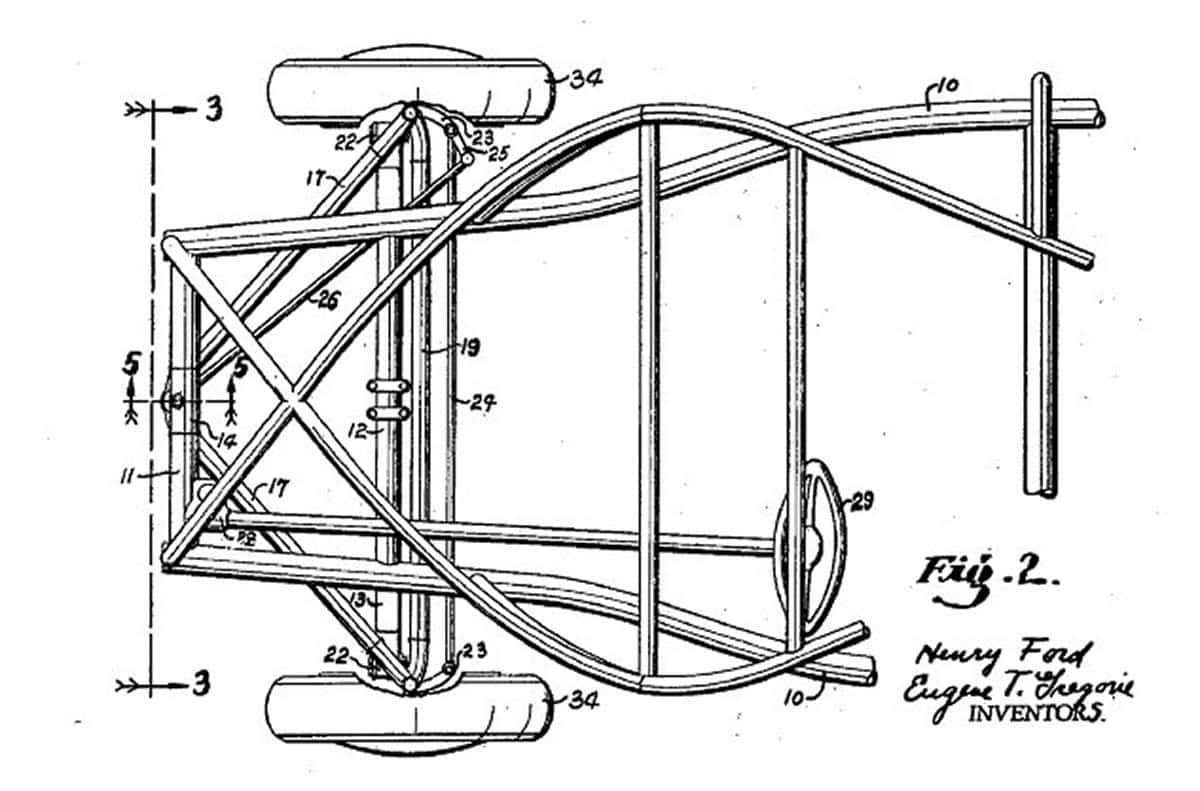

Crazy or credible? Soybean car frame patent signed by Henry Ford and Eugene Turenne Gregorie. (Courtesy: Image in public domain)

Henry Ford’s 1941 “soybean” car, which was built entirely of a plant-based plastic, was apparently motivated by a need to make vehicles lighter (and therefore more fuel efficient), less reliant on steel (which was in high demand during the Second World War), and safer too. The exact ingredients of the plastic are, however, unknown since no records were kept.

Speculation is that it was a combination of soybeans, wheat, hemp, flax, and ramie (a kind of flowering nettle). Lowell Overly, a Ford designer who had major involvement in creating the car, said it was “soybean fibre in a phenolic resin with formaldehyde used in the impregnation”. Despite being a mix of natural and synthetic materials – and not entirely made of soybeans – the car was nonetheless a significant advancement for the automotive industry more than eight decades ago.

Avoiding the “solar-panel trap”

What technological developments do we need to take materials to the next level? The key will be to avoid what I call the “solar-panel trap” and find materials that are sustainable from cradle to grave. We have to create an environmentally sustainable economic system that’s based on the reuse and regeneration of materials or products – what some dub the “circular economy”.

Sustainable composites will be essential. We’ll need composites that can be easily separated, such as adhesives that dissolve in water or a specific solvent, so that we can cleanly, quickly, and cheaply recover valuable materials from complex products. We’ll also need recycled composites, using recycled carbon fibre, or plastic combined with bio-based resins made from renewable sources like plant-based oils, starches, and agricultural waste (rather than fossil fuels).

Vital too will be eco-friendly composites that combine sustainable composite materials (such as natural fibres) with bio-based resins. In principle, these could be used to replace traditional composite materials, thereby reducing waste and environmental impact.

Another important trend is the development of novel metals and complex alloys. In addition to enhancing traditional applications, these technologies are addressing future requirements for what may become commonplace applications, such as large-scale hydrogen production, transportation, and distribution.

Soft and stretchy

Then there are “soft composites”. These are advanced, often biocompatible materials that combine softer, rubbery polymers with reinforcing fibers or nanoparticles to create flexible, durable, and functional materials suitable for use in soft robotics, medical implants, prosthetics, and wearable sensors. These materials can be engineered to possess properties such as stretchability, self-healing, magnetic actuation, and tissue integration, enabling the development of innovative and patient-friendly healthcare solutions.

Medical Magic: Wearable Electronic Materials Could Transform How We Monitor Human Health. (Shutterstock/Guguart)

And have you heard of e-textiles, which integrate electronic components into everyday fabrics? These materials could be game-changing for healthcare applications by offering wearable, non-invasive monitoring of physiological information such as heart rate and respiration.

Further applications could include advanced personal protective equipment (PPE), smart bandages, and garments for long-term rehabilitation and remote patient care. Smart textiles have the potential to revolutionize medical diagnostics, therapy delivery, and treatment by offering personalized digital healthcare solutions.

Towards “new gold”

I realize I have only scratched the surface of materials science – an amazing cauldron of ideas where physics, chemistry, and engineering work hand in hand to deliver groundbreaking solutions. It’s a hugely and truly important discipline. With far greater success than the original alchemists, materials scientists are adept at creating the “new gold”.

Their discoveries and inventions are making major contributions to our planet’s sustainable economy, from the design, deployment, and decommissioning of everyday items to finding novel solutions that will positively impact the way we live today. Surely it’s an area we should celebrate and, as physicists, become more closely involved in.

Honor Powrie is a senior director for data science and analytics at GE in Southampton, UK. She is writing here in a personal capacity.

FROM PHYSICSWORLD.COM 7-10-2025

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου