Computing memories

15 Nov 2018 Margaret Harris

Taken from the November 2018 issue of Physics World. Members of the Institute of Physics can enjoy the full issue via the Physics World app.

Margaret Harris reviews The Cryotron Files: the Strange Death of a Pioneering Cold War Computer Scientist by Iain Dey and Douglas Buck

Most children grow up hearing stories about their ancestors. For Douglas Buck, the stories were about his father Dudley – a Cold War-era scientist, computing pioneer and occasional spy who, according to family lore, might have won a Nobel prize if he hadn’t died suddenly aged just 32. Now, nearly 60 years later, Buck has teamed up with a British business journalist, Iain Dey, to write an account of his father’s life. The result is The Cryotron Files – a fascinating tale of military–industrial-complex skulduggery, which, alas, also demonstrates how hard it is to write objectively about members of one’s own family.

The first and most innocuous example of the problem appears in the book’s early chapters. Here, the young Dudley Buck comes across as an all-American, gee-whiz type straight out of a 20th-century Boys’ Own Adventure magazine. His childhood friends, several of whom were interviewed for the book, describe him as inquisitive and hard-working, with a gift for electronics and a fondness for pranks of the jolly, impish, boys-will-be-boys variety. The fact that a few of his pranks were a trifle sadistic (an electrified urinal, anyone?) goes unremarked. In the #MeToo era, it is also disconcerting to read that, as a university student, Buck essentially wiretapped a sorority house for the purpose of seducing its residents (such japes!). But ignore that. The important thing as far as The Cryotron Files is concerned is that Buck was an original thinker who caught the eye of the American military while he was still in high school and was funnelled towards computing during a stint as a Navy cadet.

The late 1940s and early 1950s were a time of “firsts” in computer science – the first stored-program machines, the first computer memories, the first transistors – and The Cryotron Filesis excellent at conveying the wide-open atmosphere of the period. Before silicon and the integrated circuit became king, engineers and physicists like Buck and his colleagues experimented with all sorts of weird and wonderful ways of creating, manipulating, storing and accessing strings of ones and zeroes.

One early machine, the EDVAC, stored data as sound waves trapped in pools of liquid mercury. Buck himself worked on a computer memory system at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) that was based on magnetic pulses in cryogenically cooled deuterium. In his spare time, Buck also dabbled in computers that mimicked the structure of the human brain, and even developed what the authors describe as “a theoretical design for a system that could manipulate ripples in Earth’s gravitational pull as a way to communicate”.

Cold warriors

The fact that so many of these wild ideas actually got funded – sometimes to the tune of millions of dollars – was down to the Cold War. By the early 1950s, the ideological struggle between the US and the Soviet Union was heating up. Pretty much every military innovation coming down the pipeline was demanding more and faster computing power, and as computer scientists scrambled to meet the demand, their efforts were boosted by an unprecedented flood of US government cash. Buck’s deuterium-based computer memory project was by no means the most outlandish scheme to benefit. In fact, it wasn’t even close. As the authors observe, “scientists elsewhere in the United States were trying to do the same thing with everything from lemon Jell-O to a particular type of hair gel called Wildroot Creme Oil”. None of those ideas took off, and neither did deuterium; instead, Buck’s grandly named Project Galatea “rumbled on for a few more years before it became overtaken by more pressing laboratory work”.

Elsewhere, however, the government’s investment paid off handsomely. From nuclear weapons and advanced radar systems to cryptography and language translation, the R&D challenges of the 1950s defence industry helped set the stage for the civilian computing revolution that followed. Indeed, America’s conflict with the Soviet Union turned out to be one of the greatest spurs to technological development the world had ever seen – albeit one that came with a tremendous price tag and the ever-present threat of nuclear Armageddon.

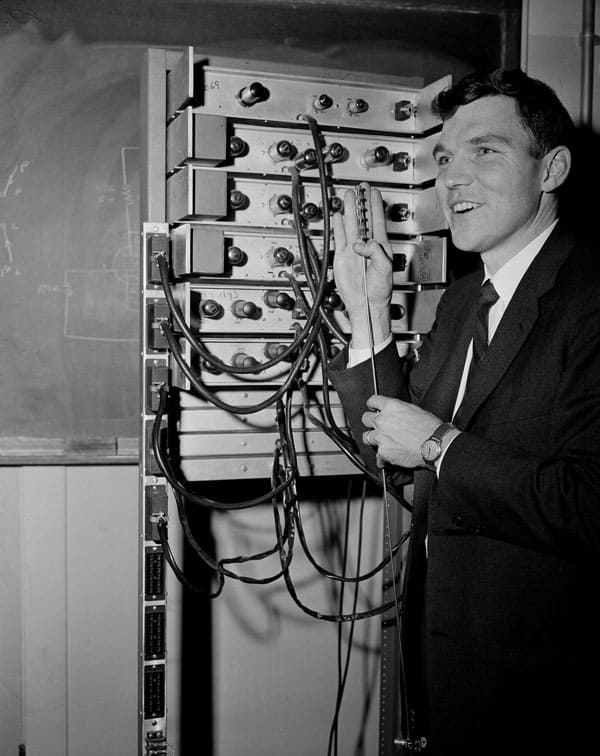

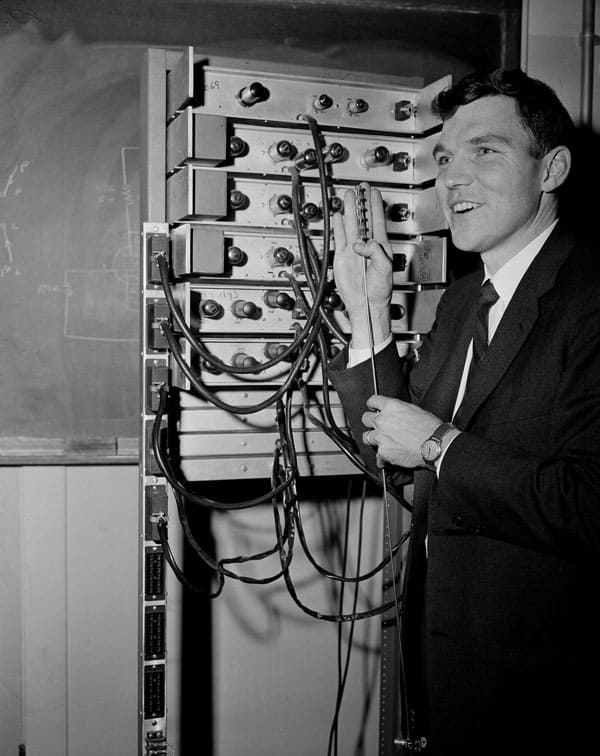

The Cryotron Files places Dudley Buck square in the midst of this hive of activity. Surviving records show that he took clandestine trips to numerous secret and semi-secret conferences. In addition to his main job at MIT, he had a side gig with the brand-new (and, at the time, still officially non-existent) US National Security Administration. By the late 1950s, he had moved on from deuterium to work on a type of computer memory based on tiny coils of superconducting wire – the cryotrons of the book’s title. And he had become sufficiently well known that, a few weeks before he died, he was one of a handful of MIT researchers picked to give laboratory tours to a delegation of visiting Russian computer scientists.

At this point in the book, questions about the authors’ objectivity start to bite. Just how important was Buck to America’s nascent national security community? And did the Soviets have something to do with his death? Both questions are difficult – maybe even impossible – to answer definitively. However, it doesn’t help that there is a clear tension between Dey’s journalistic yearning to make Dudley Buck’s story as dramatic as possible; Douglas Buck’s need to derive meaning from his father’s short life and early death; and the desire of both authors to avoid descending further down the conspiracy-theory rabbit hole than the historical record allows.

Legacy and loss

According to his author biography on the book’s dust jacket, the younger Buck “has been researching his father’s life and work since the mid-1970s and has exclusive access to Dudley Buck’s extensive archive”. In some ways, that is reassuring. If answers existed in the archives, then the authors (along with a patent expert, Alan Dewey, who is credited with additional research) would surely be well placed to unearth them. But it also suggests that Buck fils has rather a lot at stake here, and there are instances elsewhere in the book where his efforts to preserve his father’s legacy are not entirely helpful.

The book’s opening chapters, for example, contain many irrelevant (but clearly cherished) details about Buck’s family life. Conversely, and frustratingly, some technical aspects of Buck’s work are glossed over. We are told, for example, that he wrote his master’s thesis on ferroelectric memory, and that this is a key component of today’s tablets, laptops and smartphones. We are also told that the thesis “brought Buck attention from the highest levels of the military and security services”. What we aren’t told is what ferroelectric memory actually is, how it works or why the US military found it so interesting. Without that context, it is hard for the reader to grasp how important it was. Unfortunately, this same problem extends to the book’s central character.

As it happens, I also grew up hearing stories about an illustrious ancestor who died suddenly at a relatively young age. According to the diminishing circle of people who knew him, my great-grandfather – a small-town politician, pilot and born entrepreneur – was a remarkable man who would surely have been elected governor had he not been killed in a car crash at the age of 45. But the accuracy of this prognostication is impossible to verify, and it is likewise impossible to know whether Dudley Buck would have become a world-famous inventor. Sometimes, contrary to what conspiracy theorists would have us believe, the truth isn’t out there.

15/11/2018 from physicsworld.com

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου