Here comes the Sun

01 Nov 2018 Hamish Johnston

Taken from the November 2018 issue of Physics World. Members of the Institute of Physics can enjoy the full issue via the Physics World app.

Hamish Johnston reviews The Sun: Living With Our Star, an exhibition at the Science Museum in London

As winter approaches here in the UK, the dark and dreary days are a reminder of how important the Sun is to our daily lives. Fortunately, there is a bright spot at the Science Museum in London, which has just launched an exhibition called The Sun: Living With Our Star. The exhibition runs until 6 May 2019 and is a treasure trove of objects that document humanity’s fascination with the Sun through the ages.

The oldest object I spotted in the exhibition was a Babylonian cuneiform from about 750 BC that refers to sunspots – possibly observed by looking at the Sun through fog or clouds. Sunspots were not a good omen to Babylonian astronomers, who interpreted them as a sign of famine. What is clear from the exhibition is that people have obsessed over sunspots for millennia. Another stand-out object on show is a large painting of a group of sunspots done in 1864 by the Scottish amateur astronomer and industrialist James Nasmyth. The painting captures in exquisite detail the solar granules, which are created by convection currents of plasma – to me, they resemble squirming maggots. Also on display are photographs of the Sun and its spots taken in 1870 at Kew Observatory by Elizabeth Beckley, who was one of the first female employees of an astronomical observatory. Physical history: The history of solar science includes a 750 BC Babylonian record of sunspots (above) (Courtesy: Jody Kingzett, courtesy of the Science Museum Group), as well as Norman Lockyer’s helium-discovering set of prisms (below). (Courtesy: Science Museum Group Collection)

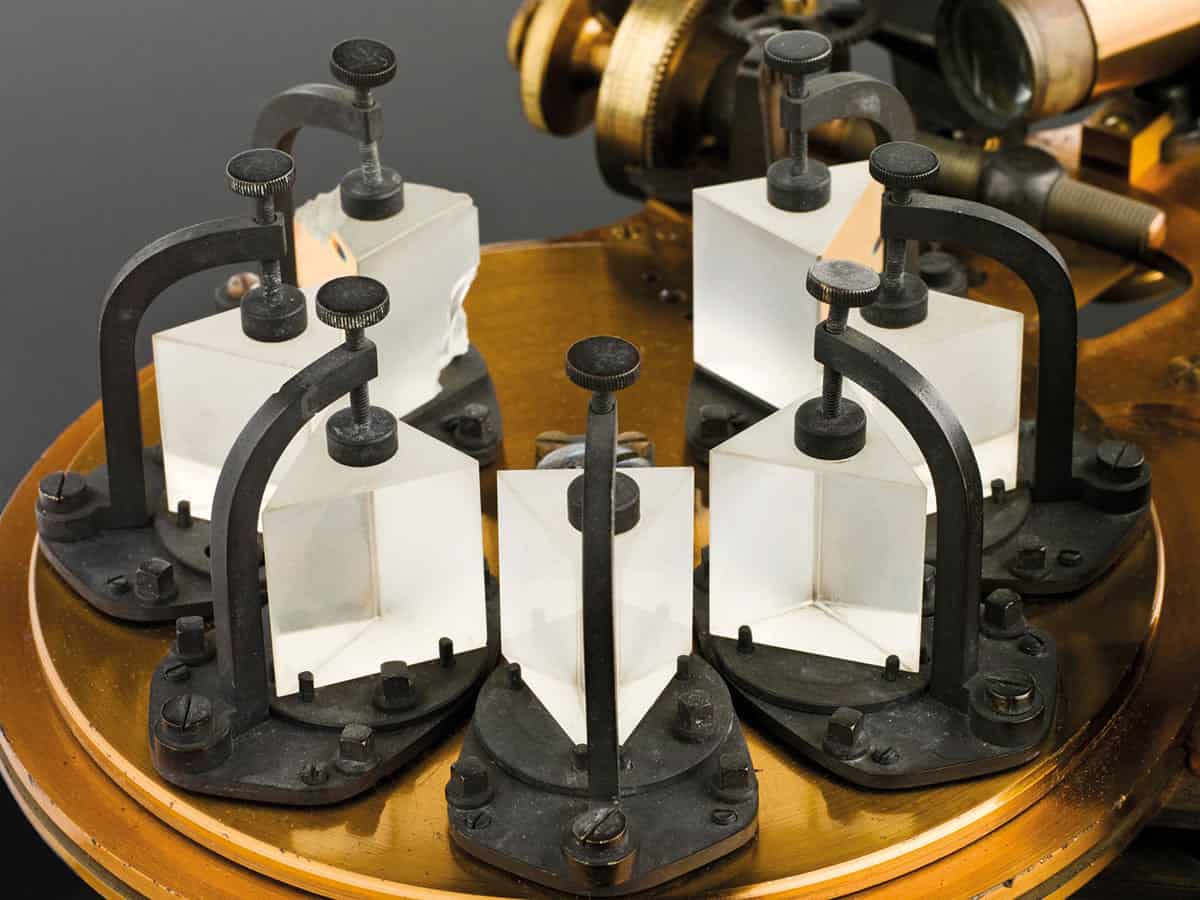

Physical history: The history of solar science includes a 750 BC Babylonian record of sunspots (above) (Courtesy: Jody Kingzett, courtesy of the Science Museum Group), as well as Norman Lockyer’s helium-discovering set of prisms (below). (Courtesy: Science Museum Group Collection)

Physical history: The history of solar science includes a 750 BC Babylonian record of sunspots (above) (Courtesy: Jody Kingzett, courtesy of the Science Museum Group), as well as Norman Lockyer’s helium-discovering set of prisms (below). (Courtesy: Science Museum Group Collection)

Physical history: The history of solar science includes a 750 BC Babylonian record of sunspots (above) (Courtesy: Jody Kingzett, courtesy of the Science Museum Group), as well as Norman Lockyer’s helium-discovering set of prisms (below). (Courtesy: Science Museum Group Collection) By coincidence, the Science Museum is next door to the Royal College of Science (now part of Imperial College London), which was home to the solar observatory where, in 1868, Norman Lockyer spotted a spectral line in sunlight that had never been seen before. He named it helium after Helios, the Greek god of the Sun. Featured in The Sun exhibition is the spectrograph that Lockyer used to discover helium – a beautiful wood and brass object with seven glass prisms arranged in a circle.

By coincidence, the Science Museum is next door to the Royal College of Science (now part of Imperial College London), which was home to the solar observatory where, in 1868, Norman Lockyer spotted a spectral line in sunlight that had never been seen before. He named it helium after Helios, the Greek god of the Sun. Featured in The Sun exhibition is the spectrograph that Lockyer used to discover helium – a beautiful wood and brass object with seven glass prisms arranged in a circle.

Fast forward to the 21st century and you will find two instruments that will be used on the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter. These are a magnetometer, which will measure the magnetic field carried by the solar wind as it rushes past the spacecraft; as well as an electron analyser, which will measure the flux of electrons within the solar wind. Like Lockyer’s spectrograph, the electron analyser is a lovely coppery colour and both modern instruments have the same high degree of craftmanship as the 19th-century instrument. Celestial wonders: Visitors to The Sun at London’s Science Museum enjoy exhibits such as a tokamak (top left), which sustained a Sun-like plasma for 29 hours. (Courtesy: Jody Kingzett, courtesy of the Science Museum Group)

Celestial wonders: Visitors to The Sun at London’s Science Museum enjoy exhibits such as a tokamak (top left), which sustained a Sun-like plasma for 29 hours. (Courtesy: Jody Kingzett, courtesy of the Science Museum Group)

Celestial wonders: Visitors to The Sun at London’s Science Museum enjoy exhibits such as a tokamak (top left), which sustained a Sun-like plasma for 29 hours. (Courtesy: Jody Kingzett, courtesy of the Science Museum Group)

Celestial wonders: Visitors to The Sun at London’s Science Museum enjoy exhibits such as a tokamak (top left), which sustained a Sun-like plasma for 29 hours. (Courtesy: Jody Kingzett, courtesy of the Science Museum Group)

Possibly the largest and surely the most hubristic object in the exhibition is a prototype tokamak that illustrates the scientific and commercial efforts to create “mini Suns” here on Earth. On loan from UK-based company Tokamak Energy, this device sustained a hot plasma for 29 hours in 2015. Those developing tokamaks and related technologies have a noble goal of generating clean energy via sustained nuclear fusion. However, a poignant reminder of the challenges they face can be found in the exhibition, where a model of the UK’s Zeta experiment is on display. Zeta gained notoriety in 1958 when its scientists announced that they had achieved fusion. On display are newspaper stories saying that fusion reactors could soon provide the energy equivalent of 10 tons of coal for just two shillings – which at the time would buy a loaf or two of bread.

If you cannot get to London for the exhibition, its chief curator Harry Cliff has written a book with Katy Barrett, who is curator of art collections at the Science Museum. It is called The Sun: One Thousand Years of Scientific Imagery and is published by Scala Arts & Heritage Publishers (£20/$28 120pp).

The Sun: Living With Our Star; Science Museum, London; Open until 6 May 2019

Hamish Johnston is the general-physics editor of Physics World

1/11/2018 from physicsworld.com

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου