Giant barocaloric cooling effect offers a new route to refrigeration

|

A new cooling technique based on dissolution barocaloric cooling could provide an environmentally friendly alternative to existing refrigeration methods. With a cooling capacity of 67 J/g and an efficiency of nearly 77%, the method developed by researchers from the Institute of Metal Research of the Chinese Academy of Sciences can reduce the temperature of a sample by 27 K in just 20 seconds – far more than is possible with standard barocaloric materials.

Traditional refrigeration relies on vapour-compression cooling. This technology has been around since the 19th century, and it relies on a fluid changing phase. Typically, an expansion valve allows a liquid refrigerant to evaporate into a gas, absorbing heat from its surroundings as it does so. A compressor then forces the refrigerant back into the liquid state, releasing the heat.

While this process is effective, it consumes a lot of electricity and offers little room for improvement. After more than a century of improvements, the vapour-compression cycle is fast approaching the Carnot limit for efficiency. The refrigerants are also often toxic, contributing to environmental damage.

In recent years, researchers have been exploring caloric cooling as a possible alternative. Caloric cooling works by controlling the entropy, or disorder, within a material using magnetic or electric fields, mechanical forces or applied pressure. The last option, known as barocaloric cooling, is in some ways the most promising. However, most of the known barocaloric materials are solids, which suffer from poor heat transfer efficiency and limited cooling capacity. Transferring heat in and out of such materials is therefore slow.

A liquid system

The new technique overcomes this limitation through a fundamental thermodynamic process known as endothermic dissolution. The principle of endothermic dissolution is that when a salt dissolves in a solvent, some of the bonds in the solvent break. Breaking those bonds takes energy, and so the solvent cools down – sometimes dramatically.

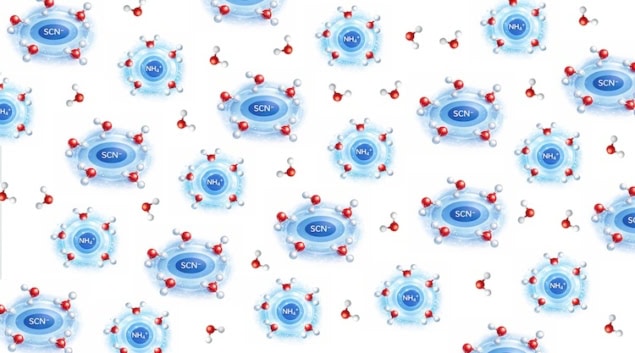

In the new work, researchers led by metallurgist and materials scientist Bing Li discovered a way to reverse this process by applying pressure. They began by dissolving ammonium thiocyanate (NH4SCN) in water. When they applied pressure to the resulting solution, the salt precipitated out (an exothermic process) in line with Le Chatelier’s principle, which states that when a system in chemical equilibrium is disturbed, it will adjust itself to a new equilibrium by counteracting as far as possible the effect of the change.

When they then released the pressure, the salt re-dissolved almost immediately. This highly endothermic process absorbs a large amount of heat, causing the solution's temperature to drop by nearly 27 K at room temperature and by up to 54 K at higher temperatures.

A chaotropic salt

Li and colleagues did not choose NH4SCN by chance. The material is a chaotropic agent, meaning it disrupts hydrogen bonding, and it is highly soluble in water, which helps maximize its concentration in the solution during that part of the cooling cycle. It also has a large enthalpy of solution, meaning that its temperature drops dramatically when it dissolves. Finally, and most importantly, it is highly sensitive to applied pressures in the range of hundreds of megapascals, which is within the capacity of conventional hydraulic systems.

Li says that his colleagues’ approach, which they detail in Nature, could encourage other researchers to develop similar techniques that likewise do not rely on phase transitions. As for applications, he notes that because aqueous NH4SCN barocaloric cooling works well at high temperatures, it could be suited to the demanding thermal management requirements of AI data centres. Other possibilities include air conditioning in domestic and industrial vehicles and buildings.

There are, however, some issues that need to be resolved before such cooling systems reach the market. NH4SCN and similar salts are corrosive, which could damage refrigerator components. The high pressures required in the current system could also prove damaging over the long run, Li adds.

To address these and other drawbacks, the researchers now plan to study other such near-saturated solutions at the atomic level, with a particular focus on how they respond to pressure. “Such fundamental studies are vital if we are to optimize the performance of these fluids as refrigerants,” Li tells Physics World.

Isabelle Dumé is a contributing editor to Physics World

from physicsworld.com 20/2/2026

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου