Schrödinger cat state sets new size record

Classical mechanics describes our everyday world of macroscopic objects very well. Quantum mechanics is similarly good at describing physics on the atomic scale. The boundary between these two regimes, however, is still poorly understood. Where, exactly, does the quantum world stop and the classical world begin?

Researchers in Austria and Germany have now pushed the line further towards the macroscopic regime by showing that metal nanoparticles made up of thousands of atoms clustered together continue to obey the rules of quantum mechanics in a double-slit-type experiment. At over 170 000 atomic mass units, these nanoparticles are heavier than some viroids and proteins – a fact that study leader Sebastian Pedalino, a PhD student at the University of Vienna, says demonstrates that quantum mechanics remains valid at this scale and alternative models are not required.

Multiscale cluster interference

According to the rules of quantum mechanics, even large objects behave as delocalized waves. However, we do not observe this behaviour in our daily lives because the characteristic length over which this behaviour extends – the de Broglie wavelength λdB = h/mv, where h is Planck’s constant, m is the object’s mass, and v is its velocity – is generally much smaller than the object itself.

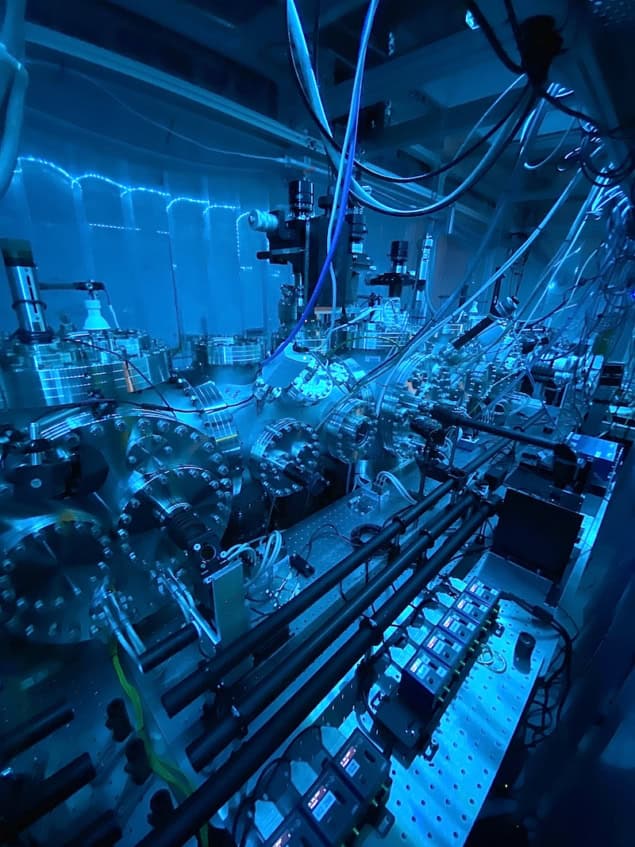

In the new work, a team led by Vienna’s Markus Arndt and Stefan Gerlich, in collaboration with Klaus Hornberger at the University of Duisburg-Essen, created clusters of sodium atoms in a helium-argon mixture at 77 K in an ultrahigh vacuum. The clusters each contained between 5000 and 1000 atoms and travelled at velocities of around 160 m s−1, giving them de Broglie wavelengths between 10‒22 femtometres (1 fm = 10-12 m).

To observe matter-wave interference in objects with such ultra-short de Broglie wavelengths, the team used an interferometer containing three diffraction gratings constructed with deep ultraviolet laser beams in a so-called Talbot–Lau configuration. The first grating channels the clusters through narrow gaps, where their wave functions expand. This wave is then modulated by the second grating, resulting in interference that produces a measurable striped pattern at the third grating.

This result implies that the clusters’ location is not fixed as it propagates through the apparatus. Instead, its wave function is spread over a span dozens of times larger than an individual cluster, meaning that it is in a superposition of locations rather than occupying a fixed position in space. This is known as a Schrödinger cat state, in reference to the famous thought experiment by physicist Erwin Schrödinger, in which he imagined a cat in a sealed box that is both dead and alive at once.

Pushing the boundaries for quantum experiments

The Vienna-Duisburg-Essen researchers characterized their experiment by calculating a quantity known as macroscopicity that combines the duration of the quantum state (its coherence time), the mass of the object in that state, and the degree of separation between states. In this work, which they detail in Nature, the macroscopicity reached a value of 15.5 – an order of magnitude higher than the best known previous reported measurement of this kind.

Arndt explains that this milestone was achieved through a long-term research programme that aims to push quantum experiments to ever higher masses and complexity. “The motivation is simply that we do not yet know if quantum mechanics is the ultimate theory or if it requires any modification at some mass limit,” he tells Physics World. While several speculative theories predict some degree of modification, he says, “as experimentalists our task is to be agnostic and see what happens”.

Arndt notes that the team’s machine is very sensitive to small forces, which can generate notable deflections of the interference fringes. In the future, he believes this effect could be exploited to characterize material properties. In the longer term, this force-sensing capability could even be used to search for new particles.

Interpretations and adventures

While Arndt says he is “impressed” that these mesoscopic objects – which are in principle easy to see and even to localize under a scattering microscope – can be delocalized on a scale more than 10 times their size if they are isolated and non-interacting, he is not entirely surprised. The challenge, he says, lies in understanding its meaning. “The interpretation of this phenomenon, the duality between this delocalization and the apparently local nature in the act of measurement, is still an open conundrum,” he says.

Looking ahead, the researchers aim to extend their research to higher-mass objects, longer coherence times, greater force sensitivity, and different materials, including nanobiological materials and other metals and dielectrics. “We still have a lot of work to do on sources, beam splitters, detectors, vibration isolation,n, and cooling,” says Arndt. “This is a big experimental adventure for us.”

Isabelle Dumé is a contributing editor to Physics World

FROM PHYSICSWORLD.COM 5/2/2026

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου