Leftover gamma rays produce medically important radioisotopes

|

The “leftover” gamma radiation produced when the beam of an electron accelerator strikes its target is usually discarded. Physicists have now found a new use for it: generating radioactive isotopes for diagnosing and treating cancer. The technique, which leverages an already running experiment, uses bremsstrahlung from an accelerator facility to trigger nuclear reactions in a layer of zinc foil. The products of these reactions include copper isotopes that are difficult to produce using conventional techniques, suggesting that the method could reduce costs and expand access to treatments.

Radioactive nuclides are commonly used to treat cancer, and so-called theranostic pairs are especially promising. These pairs occur when one isotope of an element provides diagnostic imaging while another delivers therapeutic radiation – a combination that enables precision tumour targeting to improve treatment outcomes.

One such pair is 64Cu and 67Cu: the former emits positrons that can be used to identify tumours in PET scans, while the latter emits beta particles that can destroy cancerous cells. They also have an additional clinical advantage in that copper binds to antibodies and other biomolecules, enabling isotopes to be delivered directly into cells. Indeed, these isotopes have already been used to treat cancer in mice, and early clinical studies in humans are underway.

“Wasted” photons might be harnessed

Researchers led by Mamad Eslami of the University of York, UK, have proposed a new method for producing both isotopes. Their technique exploits the fact that gamma rays generated by the intense electron beams in particle accelerator experiments interact only weakly with matter (relative to electrons or neutrons). This means that many of them pass right through their primary target and into a beam dump. These “wasted” photons still carry enough energy to drive further nuclear reactions, though, and Eslami and colleagues realized that they could be harnessed to produce 64Cu and 67Cu.

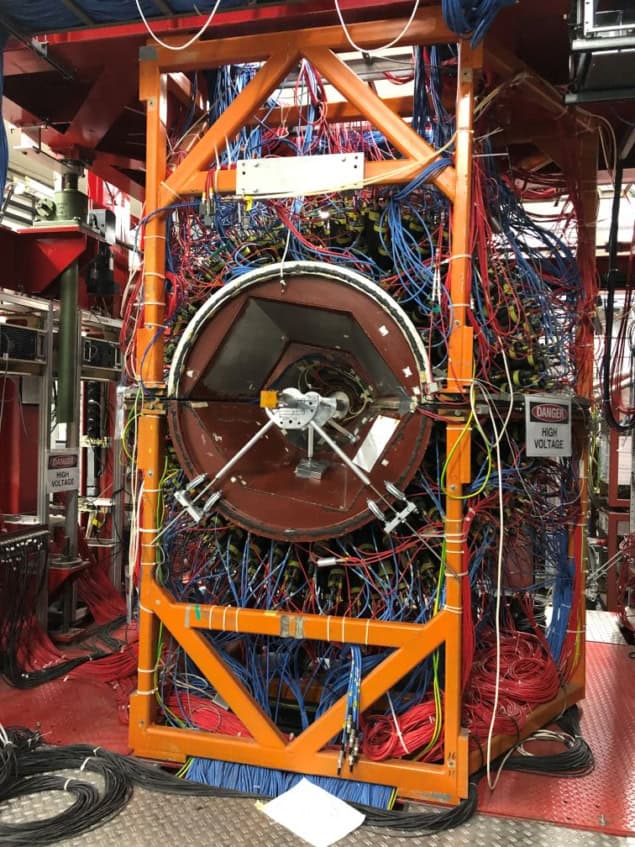

Eslami and colleagues tested their idea at the Mainz Microtron, an electron accelerator at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz in Germany. “We wanted to see whether GeV-scale bremsstrahlung, already available at the electron accelerator, could be used in a truly parasitic configuration,” Eslami says. The real test, he adds, was whether they could produce 67Cu alongside the primary experiment, which used the same electron beam and photon field to study hadron physics, without disturbing the beam or degrading beam conditions.

The answer was “yes”. What’s more, the researchers found that their approach could produce enough 67Cu for medical applications in about five days – roughly equal to the time required for a nuclear reactor to produce the equivalent amount of another important medical radionuclide, lutetium-177.

Improving nuclear medicine treatments and reducing costs

“Our results indicate that, under suitable conditions, high-energy electron and photon facilities that were originally built for nuclear or particle physics experiments could also be used to produce 67Cu and other useful radionuclides,” Eslami tells Physics World. In practice, however, Eslami adds that this will be only realistic at sites with a strong, well-characterized bremsstrahlung field. High-power multi-GeV electron facilities such as the planned Electron-Ion Collider at Brookhaven National Laboratory in the US, or a high-repetition laser-plasma electron source, are two possibilities.

Despite this restriction, team member Mikhail Bashkanov is enthusiastic about the advantages. “If we could do away with the necessity of using nuclear reactors to produce medical isotopes and solely generate them with high-energy photon beams from laser-plasma accelerators, we could significantly improve nuclear medicine treatments and reduce their costs,” Bashkanov says.

The researchers, who detail their work in Physical Review C, now plan to test their method at other electron accelerators, especially those with higher beam power and GeV-scale beams, to quantify the 67Cu yields they can expect to achieve in realistic target and beam-dump configurations. In parallel, Eslami adds, they aim to explore parasitic operation in emerging laser-plasma-driven electron sources under development for muon tomography. They would also like to link their irradiation studies to target design, radiochemistry, and timing constraints to assess whether the method can reliably and cost-effectively deliver clinically practical activities of 67Cu and other valuable isotopes.

Isabelle Dumé is a contributing editor to Physics World

from physicsworld.com 12/12/2025

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου