The fingerprint method can detect objects hidden in complex scattering media

|

Physicists have developed a novel imaging technique for detecting and characterizing objects hidden within opaque, highly scattering material. The researchers, from France and Austria, demonstrated that their new mathematical approach, which leverages the fact that hidden objects generate their own complex scattering pattern, or “fingerprint,” can be applied to biological tissue.

Viewing the inside of the human body is challenging due to the scattering nature of tissue. In ultrasound, when waves propagate through tissue, they are reflected, refracted, and scattered chaotically, creating noise that obscures the signal from the object the medical practitioner is trying to visualize. The further you delve into the body, the more incoherent the image becomes.

There are techniques for overcoming these issues, but as scattering increases in more complex media or as you push deeper through tissue, they struggle and unpicking the required signal becomes too complex.

The scientists behind the latest research, from the Institut Langevin in Paris, France, and TU Wien in Vienna, Austria, say that rather than compensating for scattering, their technique instead relies on detecting signals from the hidden object in the disorder.

Objects buried in a material create their own complex scattering pattern, and the researchers found that if you know an object’s specific acoustic signal, it’s possible to see it in the noise created by the surrounding environment.

“We cannot see the object, but the backscattered ultrasonic wave that hits the microphones of the measuring device still carries information about the fact that it has come into contact with the object we are looking for,” explains Stefan Rotter, a theoretical physicist at TU Wien.

Rotter and his colleagues examined how a series of objects scattered ultrasound waves in an interference-free environment. This created what they refer to as fingerprint matrices: measurements of the specific, characteristic way in which each object scattered the waves.

The team then developed a mathematical method that allowed them to calculate the position of each object when hidden in a scattering medium, based on its fingerprint matrix.

“From the correlations between the measured reflected wave and the unaltered fingerprint matrix, it is possible to deduce where the object is most likely to be located, even if the object is buried,” explains Rotter.

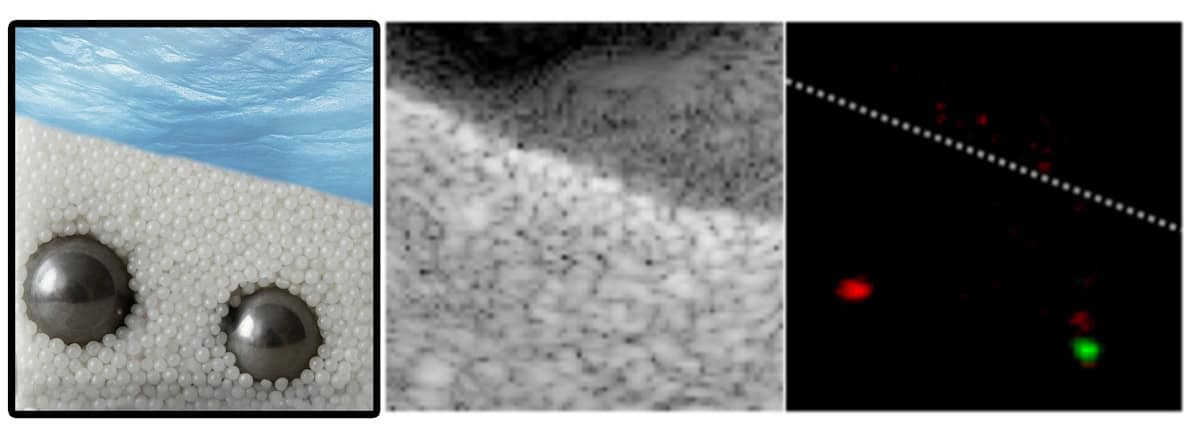

The team tested the technique in three different scenarios. The first experiment trialled the ultrasound imaging of metal spheres in a dense suspension of glass beads in water. Conventional ultrasound failed in this setup; the spheres were completely invisible. However, using their novel fingerprint method, the researchers accurately detected them.

Next, to examine a medical application of the technique, the researchers embedded lesion markers, commonly used to monitor breast tumours, in a foam designed to mimic the ultrasound scattering of soft tissue. These markers can be challenging to detect due to the random distribution of scatterers in human tissue. With the fingerprint matrix, however, the researchers say that the markers were easy to locate.

Finally, the team successfully mapped muscle fibres in a human calf using the technique. They claim this could be useful for diagnosing and monitoring neuromuscular diseases.

According to Rotter and his colleagues, their fingerprint matrix method is a versatile and universal technique that could be applied beyond ultrasound to all fields of wave physics. They highlight radar and sonar as examples of sensing techniques in which target identification and detection in noisy environments remain long-standing challenges.

“The concept of the fingerprint matrix is very generally applicable – not only for ultrasound, but also for detection with light,” Rotter says. “It opens up important new possibilities in all areas of science where a reflection matrix can be measured.”

The researchers report their findings in Nature Physics.

Michael Allen is a science writer based in the UK.

From physicsworld.com 25/12/2025

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου